Grand Egyptian Museum

Grand Staircase

The Royal Image in Ancient Egypt: Power, Divinity, and Eternity

The image of the ancient Egyptian king was meticulously crafted to project power, divine legitimacy, and the promise of eternal life. This carefully constructed persona, reflected in art, architecture, and religious practice, reveals a complex interplay between earthly authority and spiritual connection. Kings such as Senwsert III, Amenemhat III, Thutmose III, and Hatshepsut, frequently depicted in elaborate royal regalia and insignia, exemplify this deliberate projection of power and status. Their attire, meticulously rendered in sculpture and painting, served as a visual testament to their achievements and divine right to rule. The specific iconography employed – crowns, scepters, and other symbols – communicated their authority and their connection to the pantheon of Egyptian gods.

Divine Houses

This belief manifested itself tangibly through constructing and maintaining temples, shrines, and other sacred spaces – the earthly manifestations of the divine houses. These architectural projects, ranging from monumental temples like those at Karnak and Abydos to smaller, more localized shrines, were not only acts of religious devotion but also powerful displays of royal power and patronage. Their construction and decoration were vast undertakings, reflecting the king’s resources and his commitment to maintaining Ma’at, the cosmic order. The evolving architectural styles evident in these structures provide valuable insights into the changing aesthetic and technological capabilities of each era.

Kings and Gods’ Relationship

The king’s role as a divine intermediary was crucial to the royal image. He was not merely a political leader but also the earthly manifestation of Horus, the falcon-headed god, and the son of Re, the sun god – a title often rendered as Sa Re. This divine filiation was central to the king’s legitimacy, granting him access to the divine realm and the power to commune with the gods on behalf of his people.

Journey to Eternity

The ultimate goal for the ancient Egyptian kings, as for all Egyptians, was to achieve eternity – a continued existence beyond death. This aspiration found its most iconic expression in the pyramid, known in ancient Egyptian as “MR,” meaning “the place of ascent.” Far from being simply tombs, pyramids served as monumental symbols of this journey into the afterlife. Their towering presence on the landscape signified the king’s ambition to ascend to the heavens and join the gods. The meticulous planning and construction of these structures, often accompanied by elaborate funerary rituals and provisions, underscores the profound importance placed on ensuring a successful transition to the afterlife. The pyramid itself, then, served as a powerful visual representation of the king’s connection to the divine and his successful negotiation of the transition from earthly ruler to immortal being. In essence, the royal image in ancient Egypt was not just a representation of earthly power, but a carefully orchestrated performance designed to secure divine favor and ensure eternal life.

The evolution of Egypt State

The Merimde Beni-Salame

culture, flourishing in the Nile Delta from 5000 to 4200 BCE, provides valuable insight into early Neolithic life in Lower Egypt. Archaeological evidence points to a settled agricultural community reliant on the cultivation of wheat and barley, alongside the domestication of cattle and many animals. Inhabiting oval huts and employing storage pits and hearths, these people demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of resource management. The discovery of diverse pottery, tools, and figurines, particularly the varying grave goods interred with individuals, suggests a degree of craftsmanship and social stratification within the community. This culture’s establishment of a sedentary agricultural lifestyle represents a crucial step in the evolution of Egyptian civilization, bridging the gap between nomadic existence and the later, more complex societal structures of ancient Egypt.

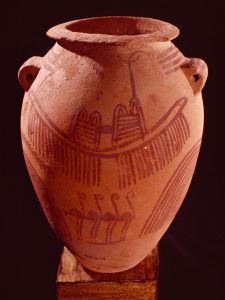

Naqada

a significant ancient Egyptian settlement located on the Nile’s east bank near Luxor, offers crucial insights into prehistoric and early dynastic Egypt. Its strategic position fostered trade, agriculture, and transportation, while its location provided natural defenses. Occupied since the Neolithic period (c. 4000 BCE), Naqada flourished during the Predynastic period (c. 4000-3100 BCE), developing complex social structures and extensive trade networks. The eponymous Naqada culture is defined by distinctive pottery, artistic motifs, and burial practices, revealed through extensive archaeological excavations. These excavations have unearthed cemeteries illustrating social hierarchies, settlement remains depicting daily life, and artifacts ranging from pottery to jewelry, illuminating the culture’s material culture and social organization. Naqada’s importance continued into the Early Dynastic period (c. 3100-2686 BCE), serving as a provincial capital and contributing significantly to Upper Egypt’s unification under Narmer. Discoveries at Naqada—including tombs, temples, residential structures, and workshops—shed light on settlement patterns, technological advancements, and social structures. Naqada’s influence extended widely, impacting the development of ancient Egyptian civilization and leaving a lasting legacy.

Tell el-Farkha: A Thousand-Year Glimpse into Early Egypt

Tell el-Farkha: A Thousand-Year Glimpse into Early Egypt

Tell el-Farkha, an archaeological site in Egypt, offers a unique and detailed glimpse into the development of early Egyptian civilization, spanning over a millennium. Its layered history, meticulously revealed through twelve seasons of excavation, reveals a complex social and political landscape that predates the well-known pharaonic era. The site’s chronology is distinctly divided into several phases, each offering invaluable insights into the evolving culture and power structures of the region. The earliest period, dating from approximately 3600 to 3300 BC, is associated with the Lower Egyptian culture of the indigenous Delta inhabitants. These early settlers were subsequently followed by migrants from Upper Egypt, individuals connected to the nascent political centers developing in the south. The site reached its zenith during the Protodynastic period and the reigns of Dynasties 0 and I (c. 3200-2950 BC), solidifying its importance as an administrative and religious center. While a decline occurred in the mid-First Dynasty, the intermittent occupation continued into the early Fourth Dynasty (Old Kingdom, c. 2600 BC). Further research is ongoing to identify the deity worshipped at this significant site Remarkable discoveries at Tell el-Farkha substantiate its significance. In 2006, excavations in the eastern portion of the site unearthed a cache predating the first Egyptian state by a century. This hoard included dozens of gold sheets, ostrich eggshells and carnelian beads, and two exceptionally large and finely crafted flint knives (30 and 50 cm long), undoubtedly possessing ritual importance. The gold sheets, once cleaned and analyzed, revealed themselves to be the remnants of two standing figures – likely depicting an early ruler and his heir – representing the oldest sculptures of this type yet found in Egypt. These artifacts are now proudly displayed in the Cairo Museum. The eastern area of Tell el-Farkha serves as a cemetery, containing over 100 graves, many of which are early mastabas from Dynasties 0 and I. These tombs are remarkably rich, filled with precious artifacts like gold and semi-precious stone ornaments, clay figurines, and tools. The vessels often bear ancient hieroglyphic signs, including the names of early rulers. The central portion of the site offers insights into the lives of ordinary people, including farmers, herders, and artisans. Despite their lower social status, they possessed a degree of wealth and participated in trade networks, as evidenced by the discovery of jewelry, copper artifacts, and imported goods. Tell el-Farkha’s unique zonal division, with distinct areas for elite residences, domestic activities, and burials, provides valuable information about the early development of Egyptian civilization. This significant site continues to shed light on the origins and growth of the pharaonic state.

Tell el-Farkha, an archaeological site in Egypt, offers a unique and detailed glimpse into the development of early Egyptian civilization, spanning over a millennium. Its layered history, meticulously revealed through twelve seasons of excavation, reveals a complex social and political landscape that predates the well-known pharaonic era. The site’s chronology is distinctly divided into several phases, each offering invaluable insights into the evolving culture and power structures of the region. The earliest period, dating from approximately 3600 to 3300 BC, is associated with the Lower Egyptian culture of the indigenous Delta inhabitants. These early settlers were subsequently followed by migrants from Upper Egypt, individuals connected to the nascent political centers developing in the south. The site reached its zenith during the Protodynastic period and the reigns of Dynasties 0 and I (c. 3200-2950 BC), solidifying its importance as an administrative and religious center. While a decline occurred in the mid-First Dynasty, the intermittent occupation continued into the early Fourth Dynasty (Old Kingdom, c. 2600 BC). Further research is ongoing to identify the deity worshipped at this significant site Remarkable discoveries at Tell el-Farkha substantiate its significance. In 2006, excavations in the eastern portion of the site unearthed a cache predating the first Egyptian state by a century. This hoard included dozens of gold sheets, ostrich eggshells and carnelian beads, and two exceptionally large and finely crafted flint knives (30 and 50 cm long), undoubtedly possessing ritual importance. The gold sheets, once cleaned and analyzed, revealed themselves to be the remnants of two standing figures – likely depicting an early ruler and his heir – representing the oldest sculptures of this type yet found in Egypt. These artifacts are now proudly displayed in the Cairo Museum. The eastern area of Tell el-Farkha serves as a cemetery, containing over 100 graves, many of which are early mastabas from Dynasties 0 and I. These tombs are remarkably rich, filled with precious artifacts like gold and semi-precious stone ornaments, clay figurines, and tools. The vessels often bear ancient hieroglyphic signs, including the names of early rulers. The central portion of the site offers insights into the lives of ordinary people, including farmers, herders, and artisans. Despite their lower social status, they possessed a degree of wealth and participated in trade networks, as evidenced by the discovery of jewelry, copper artifacts, and imported goods. Tell el-Farkha’s unique zonal division, with distinct areas for elite residences, domestic activities, and burials, provides valuable information about the early development of Egyptian civilization. This significant site continues to shed light on the origins and growth of the pharaonic state.

Food production

Ancient Egyptian civilization emerged around 3100 BC, building upon a foundation of hunter-gatherer communities and early agricultural settlements. The Nile River Valley provided fertile land for cultivating grains like emmer and barley, forming the backbone of the Egyptian diet. Bread and beer, made from these grains, were essential staples. Hunting, while important in the early stages, became a pastime for the wealthy, while the poor relied on fishing and gathering for supplementary food. Domesticated animals like cattle, sheep, and goats provided milk, cheese, and meat. Legumes, such as lentils, peas, and fava beans, complemented the grain-based diet. Fruits like dates and figs, along with aquatic plants, provided additional sustenance. The production and consumption of these foods were integral to Egyptian society, shaping its economy, culture, and religious beliefs.

The process of bread making

in ancient Egypt was a complex and labor-intensive process, involving several stages from harvesting the grain to baking the final loaf. Here’s a breakdown of the key steps:

- Grain Processing: Harvested grain was threshed, winnowed, sieved, and milled into flour.

- Dough Preparation: Flour was mixed with water and fermented to create dough.

- Baking: Dough was shaped into loaves and baked in various ways, including clay ovens and pot ovens. Egyptians produced different types of bread, such as flatbreads, leavened bread, and beer bread. Their innovative methods, including the discovery of fermentation, laid the foundation for modern bread-making techniques.

Beer Brewing

The Egyptians had a sophisticated brewing process. They would create a mash from moistened bread, often kneaded by hand or foot, and then strain it into a vat. The mash was then fermented in jars. This method, still used in some parts of Egypt and Sudan, produced a beer that was a staple beverage for many Egyptians. Brewing and baking were often depicted together in ancient Egyptian art, reflecting their interconnectedness. While actual ancient Egyptian beer has not survived, residue has been found in pottery, offering a glimpse into the past.

Ini-Sneferu-Ishetef daily life scenes

These eighteen blocks of Mural Paintings are from the tomb of Ini-Sneferu-Ishetef, Dahshur, 5th to 6th dynasty. They are believed to have been created during Egypt’s Old Kingdom, specifically between 2500 and 2200 BC, and they were made using heavy mud bricks and plaster, with some pieces weighing over 400 kilograms The paintings were originally done a secco, which means they were painted on a dry plaster base made of gypsum—a material not commonly used in modern conservation due to its challenges. These paintings had been removed from their original tomb in Dahshur in the early 1900s by a researcher named De Morgan. For many years, the paintings were stored in wooden boxes in a corridor of the Egyptian Museum without being displayed, until it was decided to move them to the new museum. Before moving the paintings, conservators used heated spatulas to apply cyclododecane sheets for protection and monitored environmental conditions and vibrations during transportation. They developed a new gypsum-based mortar that releases less water during setting, using a mix of tuff micro balloons, citric acid, xanthan gum, and a blend of ethanol and water. This mortar effectively filled gaps without causing damage from salt deposits. Various imaging techniques identified materials in the wall paintings, distinguishing Egyptian blue from other shades. A “false blue,” made from manganese black and white gypsum, was found in less significant areas, marking the oldest known instance of this pigment in ancient art. One of the most captivating scenes captured in the scene depicts a monkey stealing bananas from beneath the tomb owner’s chair. Additionally, the images showcase various fishing activities that highlight the diverse types of fish in the Nile River.

Writing and Scribes

According to scholarly resources on Ancient Egyptian culture, Hieroglyphics, referred to as “MEDU-NETJER,” translates to “sacred words.” The ancient Egyptians regarded this writing system as a divine gift from the revered god Thoth. Ancient Egyptian was a spoken and written language in Egypt for over four thousand years, symbolizing linguistic and cultural continuity. It originated with hieroglyphic writing around 3200 BCE and remained in use until the Arab conquest in 641 CE, demonstrating adaptability through various societal changes and political upheavals. The language evolved through three main stages: Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian, and Late Egyptian, and it was written in 4 inscriptions Hieroglyphic, Hieratic Demotic, and Coptic. Each stage reflects shifts in phonology, grammar, and usage context, adapting to different scripts that cater to varying levels of formality. The hieroglyphic script, first used around 3200 BCE, employed pictorial signs to represent sounds and ideas, starting with simple labels and inscriptions before developing into more complex written communication. Old Egyptian, the first fully developed grammatical stage, emerged during the Old Kingdom (circa 2600-2100 BCE). Notable examples from this period include the Pyramid Texts, the funerary inscriptions in royal tombs, that provide insight into the era’s religious beliefs and literary conventions. Additionally, autobiographies from private tombs reveal personal stories and aspirations, showcasing the language’s sophistication in articulating complex narratives and ideas.

Ancient Egyptian scribes,

known as “sš” or “sesh,” were highly respected professionals who played a crucial role in society. They were responsible for record-keeping, legal documents, and religious texts. To become a scribe, one had to undergo rigorous training in specialized schools, learning reading, writing, mathematics, and intricate hieroglyphic and hieratic scripts. Scribes held important positions within temples, government offices, and royal courts. They recorded religious rituals, managed finances, produced sacred literature, and documented royal decrees and activities. Their writing on papyrus rolls was essential for maintaining records of taxes, land ownership, and legal matters. While scribes were skilled, human error could occur during manual transcription. Mistakes like skipped lines omitted words, and misinterpretations could creep into their work. The lack of standardized spelling rules further complicated the process, leading to variations in texts. Despite these challenges, scribes were vital in preserving Egypt’s written heritage and ensuring the continuity of knowledge.

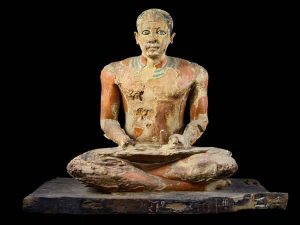

The scribe Metri

The statue portrays Metri, a scribe overseer, seated in the traditional cross-legged pose. He rests a roll of papyrus on his lap, holding it with his left hand, while his right hand clutches a pen. The statue’s body is painted reddish brown, and Metri sports short, natural hair. He wears a broad, multi-strand necklace with remnants of its original light blue, green, and white colors. His eyes feature inlays of opaque quartz for the whites and rock crystal for the pupils. Metri’s name and titles are inscribed on the wooden pedestal beneath the statue. Cross-legged seated statues are common representations of private individuals, found in various contexts such as divine temples, sanctuaries, and necropolises, across all social hierarchies. Metri held several titles, including Nome Administrator, Priest of the Goddess Maat, Greatest of the Tens of Upper Egypt, and Close Counselor. A small standing figure beside him is now nearly destroyed. Dated to the Old Kingdom, 5th Dynasty, circa 2498-2345 BC, from the Saqqara necropolis.

The statue portrays Metri, a scribe overseer, seated in the traditional cross-legged pose. He rests a roll of papyrus on his lap, holding it with his left hand, while his right hand clutches a pen. The statue’s body is painted reddish brown, and Metri sports short, natural hair. He wears a broad, multi-strand necklace with remnants of its original light blue, green, and white colors. His eyes feature inlays of opaque quartz for the whites and rock crystal for the pupils. Metri’s name and titles are inscribed on the wooden pedestal beneath the statue. Cross-legged seated statues are common representations of private individuals, found in various contexts such as divine temples, sanctuaries, and necropolises, across all social hierarchies. Metri held several titles, including Nome Administrator, Priest of the Goddess Maat, Greatest of the Tens of Upper Egypt, and Close Counselor. A small standing figure beside him is now nearly destroyed. Dated to the Old Kingdom, 5th Dynasty, circa 2498-2345 BC, from the Saqqara necropolis.

Khafre Statue

This gneiss statue depicts Pharaoh Khafre seated on a backless chair, displaying a remarkably athletic physique. The pharaoh is rendered wearing the nemes headdress, a royal beard, and a SHENDYT kilt. He holds a MEKES, likely a royal document, in his right hand resting on his knees, while his left-hand rests passively. The chair itself is decorated, with the SMATAWY unification symbol and a vertical inscription featuring Khafre’s Golden Horus and Nesw Bity titles prominently displayed on its left side. This statue was discovered in Khafre’s valley temple, primarily depicting the king himself. Around 23 statues were meticulously arranged within the temple’s interior, forming a striking display of royal power and divinity. Auguste Mariette found several statues in a pit within the temple, and Hölscher later discovered alabaster statue fragments in the emplacements. A notable feature of these statues is their diversity in both style and material. Some were seated on lion-legged thrones with back supports, while others occupied cubic seats. Additionally, the choice of materials, such as ‘Chephren diorite,’ anorthosite gneiss, greywacke, and alabaster, likely held symbolic significance, potentially reflecting the temple’s orientation and the deities associated with specific cardinal directions. The meticulous placement of these statues within the temple’s architecture suggests a deliberate arrangement, possibly linked to specific rituals or beliefs. Further research and analysis of the remaining fragments and their original positions may shed more light on this impressive statuary ensemble’s precise layout and symbolism.

This gneiss statue depicts Pharaoh Khafre seated on a backless chair, displaying a remarkably athletic physique. The pharaoh is rendered wearing the nemes headdress, a royal beard, and a SHENDYT kilt. He holds a MEKES, likely a royal document, in his right hand resting on his knees, while his left-hand rests passively. The chair itself is decorated, with the SMATAWY unification symbol and a vertical inscription featuring Khafre’s Golden Horus and Nesw Bity titles prominently displayed on its left side. This statue was discovered in Khafre’s valley temple, primarily depicting the king himself. Around 23 statues were meticulously arranged within the temple’s interior, forming a striking display of royal power and divinity. Auguste Mariette found several statues in a pit within the temple, and Hölscher later discovered alabaster statue fragments in the emplacements. A notable feature of these statues is their diversity in both style and material. Some were seated on lion-legged thrones with back supports, while others occupied cubic seats. Additionally, the choice of materials, such as ‘Chephren diorite,’ anorthosite gneiss, greywacke, and alabaster, likely held symbolic significance, potentially reflecting the temple’s orientation and the deities associated with specific cardinal directions. The meticulous placement of these statues within the temple’s architecture suggests a deliberate arrangement, possibly linked to specific rituals or beliefs. Further research and analysis of the remaining fragments and their original positions may shed more light on this impressive statuary ensemble’s precise layout and symbolism.

Hetepheres

She is the daughter of King Honi, the wife of King Sneferu, and the mother of King Khufu. On February 2, 1925, a chance discovery near the Great Pyramid of Giza led to one of the most significant archaeological finds of the 20th century. While working on the site, photographer Mohammedani Ibrahim noticed an unusual white layer of plaster, hinting at a hidden structure beneath the surface. Intrigued by this discovery, the team, even without their leader George Andrew Reisner, who was in Boston at the time, began excavation efforts. Descending into a deep, rubble-filled shaft, the team faced the daunting possibility of finding a looted tomb. However, as they delved deeper, they encountered a remarkable sight: a pristine chamber containing a sarcophagus and a wealth of ornate grave goods. This was a moment of triumph, a rare glimpse into the undisturbed past. Despite this incredible discovery, Reisner made the difficult decision to halt the excavation and reseal the tomb. This move, while controversial, was rooted in a desire to protect the site from potential damage and to ensure its preservation for future generations. The discovery of Hetepheres’s tomb remains a testament to the rich history of ancient Egypt and the careful approach required in archaeological exploration. It serves as a reminder of the delicate balance between uncovering the past and safeguarding it for the future. The tomb of Hetepheres contained significant artifacts, including an uninscribed alabaster sarcophagus, which was found empty. A canopic chest housed Hetepheres’ organs in a caustic soda solution and was secured by a seal referring to Khufu. Additional items included a gilded wooden bed, two disintegrated armchairs, a partially reconstructed canopy, and a large wooden chest filled with gold and silver decorative items, including bracelets. Numerous ceramic and stone vessels were also found, contributing valuable data for understanding Old Kingdom pottery. The find is notable for its archaeological context and the insight it provides into burial practices and royal artifacts of the era.

The Carrying (Sedan) Chair

The first recognized piece of furniture found within the shaft was a carrying chair, adorned with heavy gold sheeting. Despite being covered in gold, original wood components within the structure were found, offering insight into ancient joint-making techniques, even though the wood had shrunk and warped. The chair played a crucial role in identifying the owner of the secret tomb. Gold hieroglyphs inlaid on ebony strips at the back of the chair formed an inscription, which, despite the deterioration of the ebony, remained intact and legible. The inscription read: “Mother of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Follower of Horus, Guide of the Ruler, Favorite one, she whose every word is done for her, the daughter of the God’s body, Hetep-Heres.” This indicated that the owner was the king’s mother, specifically the chief wife of the reigning monarch, as shown by her titles. The evidence suggested that Hetep-heres, Queen of Sneferu and daughter of a former king likely named Huni, was the mother of King Cheops, who gifted her the ornate carrying chair.

The Queen’s Canopy

Archaeologists found a disassembled canopy made of 25 pieces. The supports of the canopy are carved with images of Horus, the falcon-headed god of ancient Egypt. They also discovered a gold chest that likely held the curtains for the canopy. The canopy is an impressive structure measuring 3.20 meters in length, 2.50 meters in width, and 2.20 meters in height. It features a framework of roof and floor beams, upright corner posts at the rear, and an L-shaped wooden element at the front, reflecting Old Kingdom architectural design. Ten bulbous-headed tent poles support the sides and back, while five plain roof poles span the enclosed area. The frame features evenly spaced hooks along the top edge on all four sides, which are likely intended for hanging linen curtains or mats, thereby enhancing its functionality. Additionally, copper staples attached to the outer sides of the three-floor beams are believed to have secured side curtains for added privacy. Roofing cloth was fastened with staples along the front and back beams, while hooks at both ends of the roof poles completed the enclosure.

The bed

The second piece of furniture that was identified and reconstructed was the queen’s bed, which had been placed in the tomb upside down, on top of other items. It was sheathed in gold, but the central part consisted of a wooden framework integrated into the structure, likely supporting laced rawhide webbing to provide resilience. The frame rested on four gold-sheathed lion’s legs, with the two at the foot being shorter than those at the head, creating a slope. To prevent the queen from sliding down while she slept, a footboard adorned with a pattern of faience inlays was included. We also discovered a pillow or headrest made of wood, which was covered in sheets of gold and silver. We were able to reconstruct it from the sheathing, as all the wood had decayed.

The armchair of Queen Hetepheres I

features a wooden seat and backrest framed in gold leaves and has tall, gilded arms. The backrest is supported at the back with a central support for added stability. The area between the arms, seat, and backrest is adorned with a graceful floral design, which is the main decorative element of the chair. This floral design includes three papyrus flowers, with their stems tied together by a band.

The alabaster sarcophagus,

positioned against the east wall and situated merely one meter from the chamber entrance, displayed a meticulous design intended for protection and aesthetics. With dimensions of 2 meters in length, 85 cm in width, and 80 cm in height, the coffin featured a lid that fit snugly into a rebate, showcasing a thickness of 5 cm. Notably, the box’s construction included a total thickness of 11 cm and was complemented by two hand grips on each end of the lid. Upon the chamber’s opening, distinct signs of intrusion were observed, as a metal tool had been employed to pry off the lid, evidenced by chipping on the box’s edge. The presence of alabaster chips among the linen remnants heightened suspicions of tampering, ultimately leading to a disconcerting discovery: upon removal of the lid, it was revealed that the coffin contained no remains.

Alabaster Canopic Chest.

The tomb of Queen Hetep-heres I prominently features a recess in the west wall, which accommodates her Alabaster Canopic Chest. This chest, encased within a sealed recess and resting on a deteriorated wooden sledge, measures 48.2 cm square and stands 35 cm high, characterized by its 3.5 cm thick walls and a lid of 2.8 cm thick equipped with small ledge handles. Internally, the chest is partitioned into four compartments, one of which contains decayed organic matter, while the others hold a yellowish liquid identified as a 3 percent natron solution, preserving the remains of the queen’s entrails. A central mud seal, used to secure the box, is protected by a perforated pottery lid, although the mud surface is largely decayed, it likely once bore an inscription of the mortuary workshop of Cheops, who arranged for the burial of his mother.

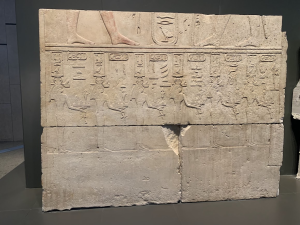

Relief fragment of Offerings Bearers, Sneferu, his Valley Temple, Dahshur

Blocks from the valley temple of Sneferu, the founder of the 4th dynasty, help us understand the symbols and functions shown in their designs. The repeated figures of women in the temple’s reliefs serve both beauty and meaning. The long rows of identical women create a rhythm that leads the viewer’s eye into the temple. These figures represent the royal estates that supported the temple, and their presence symbolizes a steady flow of offerings and devotion. This unique artistic style, with the women standing still, is different from later artworks where they are often shown in motion. In addition, the hieroglyphs on the blocks show female offering bearers, each representing a specific administrative area within Sneferu’s kingdom. These areas are organized by location and arranged to face Sneferu’s statue, emphasizing their connection to the king. This arrangement gives us important insights into the administrative structure of Sneferu’s reign and the importance of different regions.

Menkaure Alabaster Statue

depicts Pharaoh Menkaure seated on a backless chair. The king is presented with a muscular physique, wearing the nemes headdress adorned with a uraeus, a traditional long royal beard, and a short kilt called a shendyt. Menkaure’s right hand is clenched, holding the mekes, a symbolic scroll that identifies the king, while his left hand rests on his knee. Notably, his hands and feet are disproportionately larger than the rest of his body. This statue was discovered within Menkaure’s Valley temple, which features four seated alabaster figures of the king, arranged in two pairs flanking the entrance from the courtyard into the sanctuary. These statues, likely intended for funerary purposes, represent a significant artistic achievement of the Old Kingdom. The valley temple of Menkaure at Giza was meant to house numerous statues, yet it remains unfinished. Some of these statues were delivered and stored within the incomplete structure. These works included various types of royal statues, with six or more depicted as triads, highlighting the king alongside the goddess Hathor and a representative deity of Upper Egyptian nomes. Unfortunately, the intended placement of these statues remains unknow

The Osiride Royal statues,

a distinctive type of ancient Egyptian sculpture, typically depict the pharaoh standing with crossed arms and a shrouded body, leaving only the head and hands visible. These statues, often created in groups, were strategically placed at temple entrances, marking the transition from the profane to the sacred. The crossed arms, reminiscent of those seen in Sed festival statues, symbolize the pharaoh’s rejuvenation. The shrouded body, on the other hand, links these statues to various deities associated with transformation and renewal, such as Khonsu, Ptah, Min, and most significantly, Osiris. This connection suggests that the Osiride statues represent the pharaoh’s divine transformation and rebirth, mirroring the cycle of death and resurrection embodied by Osiris. While most examples from the Middle Kingdom feature the white crown of Upper Egypt, complementary statues with the red crown of Lower Egypt or the double crown likely existed, further emphasizing the pharaoh’s dual role as ruler of both Upper and Lower Egypt.

• A colossal limestone statue of King Senwosret I, representing him in the Osiride style, with the Red Crown and the idealized features characteristic of the early 12th Dynasty. The statue includes a back pillar and depicts the king wearing a divine false beard and a tight-fitting garment. His arms are crossed over his chest with closed hands. Remnants of color are still visible on his face, hands, and crown.

• A colossal limestone statue of King Senwosret I, depicted in the traditional Osiride form, characterized by the White Crown and the ideal features typical of the early 12th Dynasty. The statue features a back pillar; the king is adorned with a divine false beard and a tight-fitting garment, while his arms are crossed at his chest. Some remnants of color can still be seen on the face. The lower part of the statue is missing. As a result, reconstructing this part is necessary.

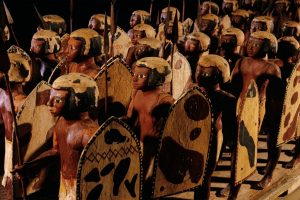

Mesheti funeral collection

The Eleventh Dynasty governor of Asyut, whose titles included “Bearer of the Royal Seal” and “Chief Priest of Wabawt,” left behind a remarkable legacy, vividly illustrated in his tomb. The collection provides invaluable insight into both the military organization and funerary beliefs of the era. His meticulously preserved tomb showcases a compelling depiction of his military forces. Models of infantry, clad in white kilts and armed with shields, demonstrate battle preparedness, while the inclusion of Nubian archers highlights the diverse composition of his army and the strategic reach of his governance. Furthermore, the presence of two intricately carved wooden coffins, inscribed with Coffin Texts, offers significant textual evidence illuminating ancient Egyptian beliefs surrounding the afterlife. This assemblage thus constitutes a singular and exceptionally well-preserved window into the political, military, and religious landscape of Eleventh Dynasty Egypt.

The Outer and Inner Coffins of Mesehti.

The outer sarcophagus, uniquely adorned with motifs inspired by the Pyramid Texts (Book of Nut), contrasts with the lavishly decorated inner coffin. A fascinating Diagonal Star Clock is positioned beneath the inner lid. However, the primary focus lies within the two coffins, where numerous Coffin Texts are inscribed. These spells are strategically placed, often repeated on different sides, creating a complex narrative about the deceased’s afterlife journey. The careful selection and arrangement of these texts within the oriented space of the coffins and the cycles of time reveal a sophisticated understanding of the afterlife and the deceased’s role within it. External texts, featuring Wedjat eyes, are rich in protective spells. Internal texts, though less frequent, focus on Nut, Isis, and Nephthys bestowing consciousness and access to the divine. The lid, back, and front walls depict the Nut’s role in creation, with the deceased identified as Nut’s child, reborn as Osiris, and inheriting divine status and eternal life.

Model of 40 Nubian archers

The Asyut model features a unique depiction of forty Nubian archers, arranged in ten distinct rows. These figures exhibit clear Nubian characteristics, including dark skin, elaborately decorated loincloths in yellow or red with pendants, and painted necklaces and anklets. Unlike typical wall scenes where Nubian archers are integrated within Egyptian battle formations, this model presents them as a separate, self-contained unit on its baseboard, distinct from the accompanying Egyptian soldiers. This unusual arrangement, necessitated by the non-combat nature of the three-dimensional figures, stands in contrast to typical portrayals and highlights the exceptional focus on this theme by the model’s creator, Mesehti, highlighting a rare representation of foreign troops in a military model.

Wooden model of 40 Egyptian soldiers

This depiction shows a cohort of forty soldiers, organized into ten ranks. Their reddish-brown skin tone, a deep tan suggestive of extensive outdoor training, is a prominent feature. Uniformity is maintained through a standardized haircut covering the ears and short kilts designed for ease of movement. Each soldier is armed with a lance and shield; however, the artist has deliberately varied the shield designs to prevent visual monotony and has also individualized the soldiers’ facial features and heights, injecting dynamism and avoiding a static representation.

Montuhotep II

The Chapel of Mentuhotep II

The limestone structure depicts the king in a smiting pose, raising a mace in one hand and a Was scepter in the other, symbolizing unification. Another scene shows him presenting bundled papyrus and lotus to Hathor. Mentuhotep II’s rule significantly impacted Egypt’s culture and religion by initiating the Middle Kingdom, a period marked by reunification and cultural revival. He reunified Egypt around 1968 BCE after defeating the Heracleopolitan kingdom, which controlled Middle and Lower Egypt, thus ending a period of disunity and conflict known as the First Intermediate Period. This reunification brought about a centralized state with Thebes as the capital, leading to increased trade and building activities, including the construction of temples and a notable mortuary complex at Thebes. Culturally, the Middle Kingdom saw the continuation and expansion of artistic and architectural traditions. Mentuhotep II’s mortuary complex at Deir El-Bahri was particularly influential, serving as an architectural inspiration for later structures, such as Hatshepsut’s temple. His reign also marked the beginning of the depiction of Amon-Re, who became a central deity in the Middle and New Kingdoms. Mentuhotep II himself was posthumously deified and worshiped, especially in the Aswan area. Religiously, the period saw the integration of Osirian beliefs into royal and non-royal funerary practices, reflecting a broader cultural base than in the Old Kingdom. This included the use of Coffin Texts, which were derived from the Pyramid Texts and inscribed on coffins during the Middle Kingdom. These developments under Mentuhotep II laid the groundwork for the religious and cultural landscape of the Middle Kingdom.

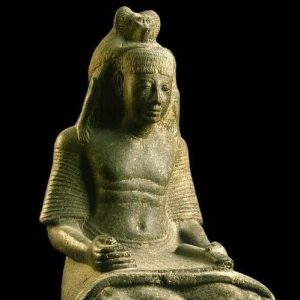

The 12th Dynasty Royal sculpture

The 12th Dynasty Royal sculpture of ancient Egypt witnessed a significant shift in royal sculpture, moving towards unprecedented realism and portraiture. Unlike the idealized representations of earlier periods, sculptures of pharaohs such as Sesostris III and Amenemhet III frequently depict aging, even careworn features. This departure from traditional aesthetic norms likely reflects a deliberate attempt to connect with the populace, presenting the king not as a divine, untouchable figure, but as one who shared in the burdens of his people – a “suffering king” concept potentially rooted in contemporary literature. This realism contrasted sharply with the monumental colossi erected for cult temples. The hard, uncompromising style of figures like Amenemhet I and Sesostris I embodies the dynasty’s assertive power and ruthless efficiency. These colossal statues, representing a first for true royal scale, powerfully communicated the pharaoh’s dominance and the strength of the state.

Amenemhat III

(1807/06-1798/97 BC) was an ancient Egyptian king who ruled during the Middle Kingdom period and was the sixth ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty. His name means “Amun is in the forefront.” He became king as a co-regent with his father, Senwosret III, which means they ruled together for a period before Amenemhat III took on a more active role alone. During Amenemhat III’s reign, which lasted 45 years, Egypt experienced a peak in its culture and economy. This impressive period was possible due to the groundwork laid by his father, Senwosret III, who had strong military and domestic policies. These policies not only regained control over Nubia but also reduced the power of local leaders known as nomarchs, creating a stable environment for Amenemhat III to rule. With this stability, Amenemhat III concentrated on ambitious construction projects, especially in the Faiyum region, which is known for its agriculture and irrigation projects. Overall, his reign is noted for its cultural and economic prosperity.

Tomb models,

prevalent during the Middle Kingdom (2055-1650 BCE), were miniature representations of everyday life intended to furnish the deceased’s afterlife. Based on the belief in a continued existence mirroring earthly life, these models provided for the deceased’s needs and ensured comfort. Common examples include agricultural models depicting farming processes to guarantee a food supply; craftsmen and workshop models representing essential skills and resources; domestic scenes showing cooking and bread-making for a comfortable home; boat models facilitating the afterlife journey; and animal figures representing food sources. These miniature replicas reflect the ancient Egyptians’ comprehensive approach to securing a prosperous and comfortable existence beyond death.

Funeral Models of El-Bersha

El-Bersheh, situated on the Nile’s east bank near Hermopolis and Tuna el-Gebel in Upper Egypt’s 15th nome, is an archaeological site renowned for its numerous rock-cut tombs dating primarily from the Old and Middle Kingdoms. The site’s most significant tombs belong to Middle Kingdom nomarchs. Nearby quarries, utilized during the 18th and 30th Dynasties, contributed to the site’s historical significance. While many tombs have been examined, revealing Coffin Texts and scenes of daily life, substantial rockfalls, stemming from ancient quarrying and subsequent seismic activity, have hindered complete excavation. A notable recent discovery includes the intact First Intermediate Period tomb of Henu, unearthed by a Belgian team in 2007. The site’s tombs originally comprised an entrance portico, chambers for offerings, and a shaft leading to a sealed burial room below, reflecting the funerary practices of the Middle Kingdom (2100-1700 BC).

• Two women are depicted as a bearer model, standing on a plinth with wide eyes. They are wearing long white one-shoulder dresses and carrying a basket of offerings on their heads. In their right hands, they hold a duck each by the wings, although one duck is now missing. The overall condition of the model is fair.

• A rectangular wooden granary model with a red door leading to a courtyard filled with workers: laborers carrying sacks up the stairs and a scribe.

• Wooden rectangular granary model with three magazines. There is a door leading to a courtyard where workers are measuring and filling the grains. Two seated men are wearing cloaks, and one worker is filling a sack with magazines.

The jewelry

The jewelry of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom (c. 2055-1650 BCE), particularly that found in royal tombs at sites like Dahshur, Lahun, and Lisht, represents a high point of ancient Egyptian goldsmithing. Exquisite examples are preserved in museums such as the Egyptian Museum in Cairo and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, showcasing advanced techniques of the period. While the abundance of precious metals is striking, the artisans’ skill is equally impressive. Goldsmiths cleverly used hollow forms and sheet gold, incorporating diverse materials – gemstones, enamel, and others – to achieve vibrant polychrome effects. The Treasure of Tod, near Luxor, further illustrates this mastery, revealing high-purity gold ingots and casting remnants alongside other materials, demonstrating sophisticated metallurgical practices. Innovative techniques such as cloisonné, wirework, and granulation, visible in pieces like Senebtysy’s headdress, added intricacy and lightness to the designs. Further research into findings from Abydos, Haraga, and other sites will illuminate the varied artistic expressions and workshop practices of this technologically advanced and creatively rich era. These exquisite gold bracelets, adorned with turquoise, lapis lazuli, and carnelian, belonged to Queen Khenemetneferhedjet Weret II, wife of Pharaoh Senwosret III. Unearthed from the pyramid complex of Senwosret III at Dahshur. The djed pillar, a symbol of stability and regeneration, is prominently featured in the design. This motif, often associated with the god Osiris, was believed to provide protection and ensure the wearer’s eternal life. The intricate craftsmanship and precious materials used in these bracelets underscore the high status of the queen and the wealth of the Twelfth Dynasty.

• The large fiancé Weskh collar is a multi-stranded necklace composed of four parallel strings of cylindrical beads. These strings are interconnected by a fifth string of similar cylindrical beads, creating a unified structure. A distinctive feature of the collar is a motif of small, drop-shaped embellishments adorning the lower edge of each of the four main bead strings. The combination of cylindrical beads and the drop motif creates a visually interesting and texturally rich piece of jewelry.

• The well-preserved Weskh collar features eight strands of cylindrical beads, each adorned with a delicate motif of small drops along its lower edge.

The officials of the New Kingdom

During the 18th and 19th Dynasties (1539-1191 BCE), Egypt became an imperial power with Amun as its chief deity. The kings attributed their successes to Amun and contributed significant resources to build and decorate his temples, leading to a rise in the influence of Amun’s priests, particularly the High Priest.

The seated scribe Amenhotep, Son of Hapu

Amenhotep acquired a broad range of titles during the prosperous reign of Amenhotep III, establishing himself as a key statesman:

• Military Titles included Chief of the Memphis Army, Chief of Recruitment, and Governor and Scribe of the Soldiers.

• Religious Titles encompassed First Prophet of Athribis, Great Celebrant of Amun, and Intendant of the Flocks of Amun.

Amenhotep began his career as a scribe of recruits, a military position under Amenhotep III. Stationed in the Nile Delta, he oversaw the strategic placement of troops at checkpoints along the Nile River. His duties included regulating maritime entry into Egypt and monitoring potential Bedouin incursions. Later, he ascended to the position of overseer of all royal works. In this role, he likely supervised the construction of monumental projects such as Amenhotep III’s mortuary temple at Thebes and the temple of Soleb in Nubia. Additionally, he oversaw the transportation of building materials for various royal projects. Beyond his administrative and military roles, Amenhotep held significant religious positions. Two statues from Thebes indicate that he served as an intercessor in Amon’s temple and oversaw the celebration of Amenhotep III’s Heb-Sed festival, a significant royal renewal rite. As a testament to his exceptional service, Amenhotep III bestowed upon him the honor of having his hometown, Athribis, beautified. Moreover, the pharaoh ordered the construction of a small funerary temple for Amenhotep next to his own, a rare privilege for a non-royal individual in ancient Egypt.

Statue of Bakenkhonsu as Standard bearer, 20th Dynasty, reign of Set Nakht Ramesses III.

The statue depicts Bakenkhonsu, the High Priest of Amon during the reign of Ramesses III. He is shown standing, wearing a long, plain kilt with wide sleeves, and holding a standard topped with a ram’s head, which is adorned with a solar disc and an uraeus. Bakenkhonsu sports a tripartite wig that reaches the back of his shoulders, with his ears left exposed, and he wears sandals on his feet. The standard of Amon features a vertical inscription of the offering formula “Htp di nsw” dedicated to the gods Amon-Re, Re-Horakhty, and Atum.

Statue of Ramessesnakht as a scribe

The High Priest Ramessesnakht is depicted sitting with his legs crossed, a typical scribe’s posture, as he focuses on writing his biography. He holds a writing tool in his left hand, ready to continue his work. A baboon, symbolizing the god Thoth, rests on his head, signifying protection, and wisdom. Thoth is associated with the moon, and knowledge, and is the patron of scribes. Ramessesnakht was married to Adjedet-Aat, the daughter of the High Priest Setau, and together they had at least two sons, Amenhotep and Nesamun, and a daughter named Tamerit.

Thutmose III

He was often hailed as one of the most formidable kings of the Eighteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt and ascended the throne in the mid-15th century BCE. His reign, lasting nearly 54 years, is characterized by significant military conquests and expansive statecraft which not only elevated Egypt’s political stature but also solidified its cultural legacy. Thutmose III’s military prowess is particularly notable. He undertook a series of campaigns in the Levant and Nubia, with over seventeen recorded military expeditions. His strategic acumen was exemplified during the Battle of Megiddo, a crucial engagement that established him as a dominant power in the Near East. This victory reflected not only his tactical brilliance but also his ability to unite and inspire his troops, ensuring loyalty and collaboration in the face of adversity. Beyond his military exploits, Thutmose III was instrumental in fostering arts and architecture, markedly expanding Egypt’s temples and monuments. His contributions included notable projects at Karnak and the construction of numerous obelisks, which symbolized the power and stability of his reign. These edifices not only served religious purposes but also acted as lasting reminders of his accomplishments. Thutmose III’s legacy extends beyond his military and architectural achievements; he is also regarded as a pivotal figure in the establishment of Egypt’s imperial ambitions. His successful campaigns laid the groundwork for Egypt’s dominance in the ancient world, setting a precedent for subsequent rulers. As a result, his reign is often seen as a zenith of Egyptian power and culture, leaving an indelible mark on the annals of history.

Hatshepsut: A Remarkable Female Queen of Ancient Egypt

Hatshepsut, one of the most prominent and influential pharaohs of ancient Egypt, defied traditional gender roles and left an indelible mark on the history of the New Kingdom. Reigning during the 18th Dynasty, she ascended to power in the early 15th century BCE, initially as a regent for her young stepson, Thutmose III. However, Hatshepsut’s ambition led her to declare herself pharaoh, a title traditionally reserved for men. This significant departure from the norms of her time underscores her extraordinary aptitude for leadership and statecraft. Her reign, lasting for approximately twenty-two years, was marked by unprecedented prosperity, expansive trade, and monumental architectural achievements. Hatshepsut’s ambitious trading expedition to the land of Punt exemplified her commitment to enhancing Egypt’s wealth and influence. This endeavour not only expanded Egypt’s trade routes but also enriched the nation with exotic goods, contributing to the flourishing of the economy. In addition to her economic initiatives, Hatshepsut was a patron of the arts and architecture. She commissioned numerous projects, most notably her mortuary temple at Deir El-Bahari, which stands as a testament to her vision and engineering capabilities. This temple, adorned with intricate reliefs and inscriptions, not only served a religious purpose but also proclaimed her achievements and divine right to rule. Despite her notable contributions, Hatshepsut faced challenges in solidifying her legacy in a male-dominated society. After her death, Thutmose III sought to diminish her influence by erasing her name and images from the historical record. Nonetheless, modern scholarship has revived interest in Hatshepsut, acknowledging her as a pioneering figure in ancient history

On the northern wall of the second terrace, the Punt colonnade next to Hathor’s temple depicts Queen Hatshepsut’s journey to the Land of Punt in 1480 BC to acquire trees. She oversaw the expedition’s preparations, which were led by her royal advisor Nehsi and aimed to bring back myrrh, incense, gold, and leopard skins. The mission utilized five ships, each 21 meters long and carrying 210 crew members, including sailors, rowers, workers, and soldiers. They also transported numerous Egyptian goods for trade, including a statue of Amun. Upon reaching Punt, the Egyptians exchanged gifts with the local king and Queen Ity, and successfully returned with 31 live trees, marking the first recorded attempt to plant foreign species in Egypt. Hatshepsut planted these trees in her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, where she commemorated the journey and reestablished trade networks disrupted during the Hyksos invasion. The expedition’s route went from the Nile to Memphis, through the Mediterranean to the Red Sea via a renovated canal. The precise location of Punt is debated, with some archaeologists suggesting it corresponds to present-day Somalia, while its name was recorded as early as 2500 BC and disappeared around 1000 BC.

On the northern wall of the second terrace, the Punt colonnade next to Hathor’s temple depicts Queen Hatshepsut’s journey to the Land of Punt in 1480 BC to acquire trees. She oversaw the expedition’s preparations, which were led by her royal advisor Nehsi and aimed to bring back myrrh, incense, gold, and leopard skins. The mission utilized five ships, each 21 meters long and carrying 210 crew members, including sailors, rowers, workers, and soldiers. They also transported numerous Egyptian goods for trade, including a statue of Amun. Upon reaching Punt, the Egyptians exchanged gifts with the local king and Queen Ity, and successfully returned with 31 live trees, marking the first recorded attempt to plant foreign species in Egypt. Hatshepsut planted these trees in her mortuary temple at Deir el-Bahari, where she commemorated the journey and reestablished trade networks disrupted during the Hyksos invasion. The expedition’s route went from the Nile to Memphis, through the Mediterranean to the Red Sea via a renovated canal. The precise location of Punt is debated, with some archaeologists suggesting it corresponds to present-day Somalia, while its name was recorded as early as 2500 BC and disappeared around 1000 BC.

The Legacy of Akhenaten: A Revolutionary Pharaoh

Akhenaten, also known as Amenhotep IV, ascended to the throne of ancient Egypt during the 18th Dynasty, around 1353 BCE. His reign, which lasted for approximately 17 years, is often regarded as one of the most transformative periods in ancient Egyptian history. Akhenaten is best known for his radical departure from traditional polytheism and the introduction of monotheism through the worship of Aten, the sun disc. This profound shift not only influenced religious practices but also had lasting impacts on art, culture, and governance. Akhenaten’s most significant reform was the establishment of Atenism, wherein he promoted the worship of Aten as the sole deity, relegating the worship of the many traditional gods of Egypt. This break from established religious norms disrupted centuries of worship practices and altered the sociopolitical landscape. Akhenaten’s monotheistic approach laid a foundation for later religious innovations in the region, although it was not sustained beyond his reign. In addition to his religious reforms, Akhenaten’s reign marked a notable evolution in artistic expression. Art produced during this period became increasingly naturalistic, reflecting a departure from the rigid conventions of previous styles. This artistic shift is epitomized in the reliefs found in Akhetaten, the city he established as the center of his new religious movement. The depictions represented intimacy and realism, often portraying the royal family in candid moments, a stark contrast to the idealized forms of previous eras. However, with the death of Akhenaten, the monotheistic religion he championed quickly fell into obscurity. Successors like Tutankhamun reinstated polytheism and restored traditional practices, signaling a return to established norms and an eventual rejection of Akhenaten’s radical changes. The historical repercussions of his reign were long-lasting, as Egypt subsequently shifted back to a society rich in polytheistic traditions.

Akhenaten constructed a remarkable temple at Karnak dedicated to the solar deity Aten. This temple was larger than the existing Amun temple and reflected Akhenaten’s deep devotion to Aten, leading him to adopt the name Akhenaten and reform traditional festivals to exclusively celebrate Aten as the sole god. The temple and its accompanying structures were built using small sandstone blocks called talatat, which measured approximately 52 x 22 x 26 cm. These lightweight blocks allowed for rapid construction and could be easily managed by a single laborer. The talatat were characterized by their size and featured the distinctive Amarna style of relief carvings, making them integral to the temple’s design. However, after Akhenaten’s reign, he was labeled a heretic, resulting in the dismantling of his temples dedicated to Aten. Many of these talatat blocks were repurposed in later constructions and often hidden within the foundations of new buildings, including the Aten temple at Karnak. Over time, as the Amun temple began to deteriorate, excavations led by French archaeologists starting in the 1840s unearthed a significant number of talatat, totaling over 30,000 by the 1960s. During the 1950s and 60s, these blocks were secured for preservation, and further restoration efforts from the 1960s to the 1980s uncovered many more. In total, approximately 50,000 talatat have been discovered at Karnak, which represents just a fraction of the original materials used for the Aten temple.

Akhenaten constructed a remarkable temple at Karnak dedicated to the solar deity Aten. This temple was larger than the existing Amun temple and reflected Akhenaten’s deep devotion to Aten, leading him to adopt the name Akhenaten and reform traditional festivals to exclusively celebrate Aten as the sole god. The temple and its accompanying structures were built using small sandstone blocks called talatat, which measured approximately 52 x 22 x 26 cm. These lightweight blocks allowed for rapid construction and could be easily managed by a single laborer. The talatat were characterized by their size and featured the distinctive Amarna style of relief carvings, making them integral to the temple’s design. However, after Akhenaten’s reign, he was labeled a heretic, resulting in the dismantling of his temples dedicated to Aten. Many of these talatat blocks were repurposed in later constructions and often hidden within the foundations of new buildings, including the Aten temple at Karnak. Over time, as the Amun temple began to deteriorate, excavations led by French archaeologists starting in the 1840s unearthed a significant number of talatat, totaling over 30,000 by the 1960s. During the 1950s and 60s, these blocks were secured for preservation, and further restoration efforts from the 1960s to the 1980s uncovered many more. In total, approximately 50,000 talatat have been discovered at Karnak, which represents just a fraction of the original materials used for the Aten temple.

Amun and Mut statues

The statues of Amun and Mut have been extensively restored, consisting of 79 pieces. The goddess’s head was originally excavated by Auguste Mariette at Karnak in 1873, with additional parts discovered over the years during excavations at the Temple of Amun-Re and sent to the Egyptian Museum for reassembly. The statue’s base is inscribed for King Horemheb, noted as beloved of Mut and Amun. The sculpture was damaged in the Middle Ages by stone robbers who quarried blocks from its back slab and base and hollowed out a basin in the back of the throne. His throne features decorations on both sides representing the unification of the Two Lands (sema-tawy) and is inscribed with the names of the gods. Next to Amun is his name and title: Amun-Re, Lord of the Thrones of the Two Lands, who lives in Karnak.

Amun (Amon)

is an ancient Egyptian god whose prominence grew during the New Kingdom in Thebes. His name means “hidden,” and he is associated with the Hermopolitan myths of life. He was first mentioned in pyramid texts. The earliest evidence of Amun in Thebes is an inscription by the Sixth Dynasty nomarch Rehuy, who served him. As Thebans gained political power, the cult of Amun flourished, particularly during the New Kingdom. However, the earliest significant evidence of Amun’s evolution is found in the White Shrine at Karnak, built by King Senusret I of the Middle Kingdom. During this period, Amun absorbed some attributes from other deities and was even said to have given birth to himself, setting him apart from other gods. He was originally part of the Ogdoad of Hermopolis and later became associated with the Primeval Mound of Memphis. According to myth, he created other gods before ascending to the heavens as Re, emerging from a lotus flower. Amun is usually depicted as a handsome young man or a ram with curled horns. New Kingdom rulers carried his banners, and his temple in Thebes received tributes from many lands. Revered as “the Greatest of Heaven, Eldest of Earth,” priests composed heartfelt hymns in his honor.

Mut,

whose name is translated as “Mother,” was the great mother and queen of the gods who ruled Thebes. Although her origins are unclear, her popularity increased over time with her cult. Mut took on a crucial role as the consort of Amun and the mother of Khonsu, especially from the reign of Amenhotep III onward. She is often depicted wearing the Double Crown, which symbolizes her responsibility for protecting the kingship and the king himself. The primary center of her cult was located at South Karnak, connected to the Amun Precinct by an avenue lined with rams. Her hieroglyph was the vulture, and she was known as “the Mistress of the Double Crown of Egypt.” At Kharga Oasis, she is depicted with a lion’s head, further emphasizing her power. Additionally, she was celebrated as “the Mistress of the House,” highlighting her role as a patroness of children and motherhood.

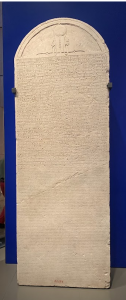

Restoration Stela

Bearing profound significance serves as a crucial historical record illuminating the reign of Tutankhamun. Discovered by Georges Legrain in 1905 in the Temple of Amun at Karnak, this stela emerges as a reflection on the tumultuous consequences of Akhenaten’s reforms in ancient Egypt. It poignantly recounts the adverse effects these changes had on the religious and cultural landscape, notably the deterioration of temple practices, the abolishment of godly cults, and the apparent abandonment by the deities themselves. The stela commences with critical details regarding Tutankhamun’s royal titulary and the specific date of the restoration events, delineating the ceremonial aspects of his reign. It invokes the tutelary deities, establishing the divine protection afforded to the king and his land, while simultaneously emphasizing the king’s divine birth through various exalted epithets. The narrative transitions into a somber reflection on the prior conditions of turmoil the land endured during the Amarna Period, elucidating how the gods felt neglected and forsaken amid the widespread distress. Amidst this historical context, the stela asserts Tutankhamun’s coronation, marking the advent of his reign as a herald of renewal. It extols the restoration of the sacred images of Amun and Ptah, essential symbols of spiritual rejuvenation, alongside the revival of temples and priesthoods that had languished. The construction of divine barks for religious ceremonies further underscores the king’s commitment to restoring Egypt’s spiritual integrity. Moreover, the stela reveals the joy expressed by both the gods and the populace following Tutankhamun’s reforms, portraying a narrative of reconciliation between the divine and the earthly. The document underscores the gifts bestowed upon the king by the temple gods, reinforcing his favored status. It culminates with the sessions of the royal court, where decisions of national importance were made, showcasing the king’s strength and wisdom through his various epithets.

Animal Cult

In ancient religious practices, animals played crucial roles as manifestations of gods or as offerings. They participated in festivals and divination rituals. Different animal materials—such as hides, bones, and feathers—were used to create various religious objects, including amulets and instruments, for temple and private practices. Animal sacrifice was vital for sanctifying temples and tombs, with cattle remains often placed at structural corners. In both Egyptian and Nubian cultures, bucrania (ox skulls) adorned tombs as symbols of wealth and protection. Funerary offerings, including meat and poultry, were believed to sustain the deceased in the afterlife. Many of the gods and goddesses of ancient Egypt were depicted in animal forms. Notable examples include the cat of Bastet, the ram of Khnum, the cow of Hathor, and the falcon of Horus, which illustrate the deities’ iconic theriomorphic representations. Additionally, Amun could take the form of a goose, and many deities had bovine forms. Our best evidence regarding the rituals associated with these sacred animals comes from the latter.

Thoth

is the Egyptian god of writing, magic, wisdom, and the moon, and he is a central figure in ancient Egyptian mythology. He is believed to have either created himself or been born from the seed of Horus. Thoth embodies the principles of ma’at, which represents divine balance, and he is closely associated with the goddess Ma’at, who is sometimes regarded as his wife. The worship of Thoth began in Lower Egypt during the Pre-Dynastic Period and continued through the Ptolemaic Period, making him one of the most enduring deities in Egyptian history. Thoth is commonly depicted with the head of an ibis or as a baboon, and he was revered by scribes. They honored him by pouring a drop of ink before starting their work. In the judgment of the dead, Thoth plays a vital role alongside Osiris in the Hall of Truth. He assists souls who are concerned about their passage into the afterlife. His primary consort is Seshat, the goddess of writing and libraries. Thoth is associated with the baboon and ibis found in the catacombs at Tuna el-Gebel. The baboons buried in these catacombs likely represent a series of sacred animals connected to Thoth. Additionally, the catacombs contain a significant number of embalmed ibises, which reflect another category of ritual animals known as votive creatures.

Bastet,

primarily worshipped in Bubastis, a key city in the southeastern Nile Delta, has its earliest references in the galleries beneath the step pyramid of Djoser at Saqqara, dating back to around 2800 BCE. Archaeological findings include numerous stone vessel sherds from 2nd dynasty burials, some inscribed with mentions of deities, including Bastet, depicted as a lioness. Initially, Bastet may have functioned as the deity of the royal residence, and her name is thought to derive from the term for an ointment jar. This connection suggests she symbolized both protective qualities and royal regalia, embodying the powerful nature of a divine lioness aligned with royal ideology. The character of feline goddesses, particularly Bastet, evolved, reflecting a more ambivalent nature. In later periods, Bastet was reimagined as a gentler figure, symbolized by a cat, which represented a more approachable and less threatening aspect compared to a lioness. This transformation coincided with the Middle Kingdom, where cats, though still resembling their wild ancestors, began to appear as pets in tomb paintings, indicating a shift in their cultural significance.

Serapis

was a Greco-Egyptian god, first venerated in Memphis alongside the sacred bull, Apis. He emerged during the reign of Ptolemy I Soter (305–284 BCE), who sought to harmonize Greek and Egyptian religious practices. This syncretic deity combined elements from the Egyptian gods Osiris and Apis with features of Greek deities like Zeus and Hades, promoting cultural unity under Ptolemaic rule. Originally viewed as a god of the underworld, Serapis was redefined in a Hellenic context by Ptolemy I, who established his cult in Alexandria. The Serapeum became the primary temple dedicated to him, where his statue portrayed him as a majestic, bearded figure seated on a throne, accompanied by Cerberus and holding a scepter. Over the years, Serapis was not only worshipped as a sun god—often called “Zeus Serapis”—but also celebrated as a deity of healing and fertility. His influence expanded throughout the Mediterranean and into Rome, particularly in significant commercial hubs. Among the Gnostics, Serapis represented the concept of the universal godhead. However, his worship declined notably when Theophilus and his followers destroyed the Serapeum in 391 CE, signaling a major shift towards the rise of Christianity within the Roman Empire.

Isis Cult

For the ancient Greeks, Isis was appealing because their pantheon lacked a goddess who embodied multiple qualities: healer, protector, fertility symbol, mother, and one who promised life after death. Although individual goddesses reflected some of Isis’s attributes, the Greek interpretation allowed her worshippers to adapt her to Greek culture, which helped her cult spread from Delos to Italy and eventually back to Egypt as a Hellenized figure during the Roman period. Isis’s healing powers attracted the Greeks, but her connection to the Osiris myth presented a paradox; they generally did not worship gods associated with death and had reservations about resurrection. As a result, her companion, Osiris, was often excluded from her worship outside of Egypt. In Hellenized contexts, Isis’s role in funerary practices diminished, and her iconography and temples evolved away from pharaonic styles. Consequently, the cult of Osiris became rare outside of Egypt, and where it did appear, his identity was often transformed, frequently merging him with Dionysos. In Ptolemaic Egypt and throughout the Mediterranean, Isis gained a new consort, Serapis, who combined elements of Osiris with other deities.

Harpokrates,

originally an Egyptian deity, expanded his influence during the Graeco-Roman period through associations with various gods, gaining popularity particularly in Ptolemaic Egypt. He was regarded as the son of Isis and Serapis, with a well-established temple in Alexandria called Harmotieum. Often depicted alongside Isis, he was known as “the favorite god of the household and the lower classes.” Numerous terracotta figurines were found in domestic settings, highlighting his connection to family life. His depictions frequently included other deities like Anubis and Dionysus, underscoring his multifaceted nature. As the child form of Horus, Harpokrates served as a protector of children and was linked to agricultural productivity, celebrated in the Harpokratia for his diverse roles as a guardian and fulfiller of dreams.

Horus and King Nectanebo II- granite- 30 dynasty

From the earliest dynasties, ancient Egyptians viewed their king as a divine figure; The king embodied the living Horus on earth, who served as a protector of the human monarch. This association between king and God is illustrated in statuary as early as the 4th Dynasty, notably in a famous seated statue of Khafre in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, where a falcon spreads its wings protectively around the back of the king’s head. Roughly two thousand years later, this same theme reemerges in a statue of Horus accompanying King Nectanebo II, the last ruler of the 30th Dynasty. King Nectanebo II emphasized a strong connection with the falcon god Horus, often merging his identity with that of the deity. He was the center of a cult that referred to him as “Nectanebo-the-Falcon,” highlighting the significant relationship between his kingship and the symbolism of the falcon. Nectanebo II, originally named Nakhthoreb, became the last native ruler of Egypt after usurping the throne from his uncle Teos, who the royal family deemed unfit. His reign lasted from 360 B.C.E. until his death. Nectanebo II was the grandson of Nectanebo I and the nephew of Teos, and he was declared rightful ruler by his father, Tjahepimu, during Teos’s military campaign. With the support of the Spartan ruler Agesilaus, he successfully overthrew Teos, who subsequently fled to Persia. In 350 B.C.E., Nectanebo II faced an attack from Artaxerxes III Ochus but managed to repel the Persian forces. Following this victory, he focused on revitalizing the Nile Valley, undertaking significant construction projects in cities and temples such as Behbeit el-Hagar, Erment, Bubastis, and Saqqara, and he even built a gate at Philae. He was also deeply involved in the bull cults of his time, notably burying sacred animals at Erment and restoring the Bucheum. However, in 343 B.C.E., Nectanebo II was again attacked by Artaxerxes III Ochus and was defeated at Pelusium. He fled to Nubia, later returning to Sebennytos. Upon his death, he was supposed to be buried in Sebennytos) Samannud (, or the city of Rhakotis, which would become Alexandria. Although a tomb was prepared in Sais, it remained unused, and his black granite sarcophagus eventually found its way to Alexandria as a public bath.

Nes-Ptah’s sarcophagus with an anthropoid lid

Nes-Ptah was a nobleman and the son of Montumhat, the overseer of Thebes. His sarcophagus, inscribed with hieroglyphic texts, weighs an impressive five tons. The richness and quality of the sarcophagus reflect Nes-Ptah’s economic and social status. Montumhat, his father, was a wealthy and influential mayor of Thebes and Governor of Upper Egypt, playing a vital role in the city’s reconstruction after its destruction by the Assyrians. His significant power in Thebes allowed him to present himself as a king in his statues, aligning with the Egyptian tradition where kings were viewed as both rulers and divine figures. This portrayal emphasized calmness and stability—traits associated with the Nile. All of the Montumhat statues were created in the Old Kingdom style. Active during the Twenty-Fifth Dynasty (c. 700–650 BC) and a contemporary of King Taharqa, Montumhat held the title of Fourth Priest of Amun but was effectively the ruler of Upper Egypt. He was a key builder of Theban temples during the Late Period, contributing to projects for both Taharqa and himself. Amid the challenges of Taharqa’s reign, which included Assyrian invasions, Montumhat skillfully negotiated with the Assyrians to secure his position. His impressive tomb (TT 34) at Deir el-Bahri features a grand sun court.

Arsinoe II,

a prominent figure in the Hellenistic era, was a strategic player in the Ptolemaic dynasty. Born around 316 BC, she was the daughter of Ptolemy I Soter and Berenice. Through a series of politically motivated marriages, including unions with her half-brother and full-brother, she solidified Ptolemaic control over Egypt. Her influential role and power made her one of the most recognized women of her time. She Married Ptolemy II, her full brother. They ruled together, and both adopted the title Philadelphus, meaning “Brother-Loving” and “Sister-Loving.” This practice of marrying close relatives became common among their successors and was even adopted by ordinary Egyptians despite not being customary in previous Egyptian royal families or among the general population. Arsinoe II’s influence extended far beyond her lifetime. She wielded considerable power over her husband, Ptolemy II, shaping his political choices. After her untimely death, Ptolemy II, overwhelmed by grief, deified her, drawing inspiration from ancient Egyptian religious practices. This act not only honored her memory but also strengthened his connection with the Egyptian people. The cult of Arsinoe II thrived, with priestesses carrying out sacred rituals and commemorating her legacy. She was closely linked to revered Greco-Egyptian goddesses like Aphrodite, Isis, and Hathor and was even worshipped as Aphrodite herself.

Canopus decree